The circus horse doesn’t exist, but without the horse, the circus wouldn’t exist. The circus, which enchants young and old alike, has been around for less than two and a half centuries; fortunately, man didn’t wait for its advent to shape and develop the different breeds of horse that express themselves under the big tops.

The circus begins on horseback

The true creator of the circus in 1768, twenty-six-year-old English cavalry sergeant-major Philip Astley’s first partners were his horses. That’s why any circus worthy of the name must include a dirt and sawdust ring, specifically designed for equestrian acrobatics, historically the first exercise performed in this type of establishment. It was the same man, in the guise of a ringmaster guiding his horses around him with the help of a whip held at arm’s length, strap deployed, who designed the circular scenic space with a radius of 6 m to 6.50 m that constitutes the circus ring.

As early as 1770, Philip Astley’s show combined his feats as an equestrian and acrobat with those of jugglers, acrobats, and rope dancers, all of whom performed at fairs and funfairs. From the origins of the circus to the circuses of today, if the horse has lost the leading role, at least its imprint is indelible: the universal size of every circus ring in the world is 12 to 13 m in diameter (40 feet) … including Bamum’s, which has three!

The first acrobatic horsewomen, including Madame Astley herself, soon appeared in the ring, and by 1774, Parisians were able to admire them. The talents of Philip Astley’s son John, born in 1770, as a “horse dancer at full gallop” enabled him to appear in Paris in 1782. In 1788, John took over management of the English Amphitheater (the first Parisian circus created in the Faubourg du Temple six years earlier by his father), featuring Antonio Franconi, his sons and their 20 horses. This Franconi, a Venetian by birth, took advantage of Astley’s return to England during the Revolution to take over his establishment, which in 1795 became the Franconi Amphitheatre, where, for the first time in the ring, presented by his son Henri, high school dressage appeared. In 1806, Henri, his brother Laurent and their respective wives – Catherine Cousis and Marie Lequien, the first to perform as panel horsewomen (horsewomen dressed in an antique-style tunic or ballerina tutu, perched on a padded panel attached to the horse’s back, where they perform dance steps and ribbon or hoop jumps) – created the first establishment in Paris to bear the name of circus: the Cirque Olympique. This was followed by the Nouveau Cirque Olympique, where, in 1818, English acrobat Andrew Ducrow rose to fame. It was he who created the St. Petersburg Courier, otherwise known as La Poste, an act in which, standing on two horses at full gallop, the rider grabs the reins folded over the withers of eight horses which, one by one, pass under him between the two carrying horses, enabling him to lead his spirited crew on the long reins in a wild race. In 1999, Maud Gruss, an extraordinary eighteen-year-old horsewoman and worthy daughter of her father Alexis Gruss, brought this exercise to its climax with seventeen horses in the ring.

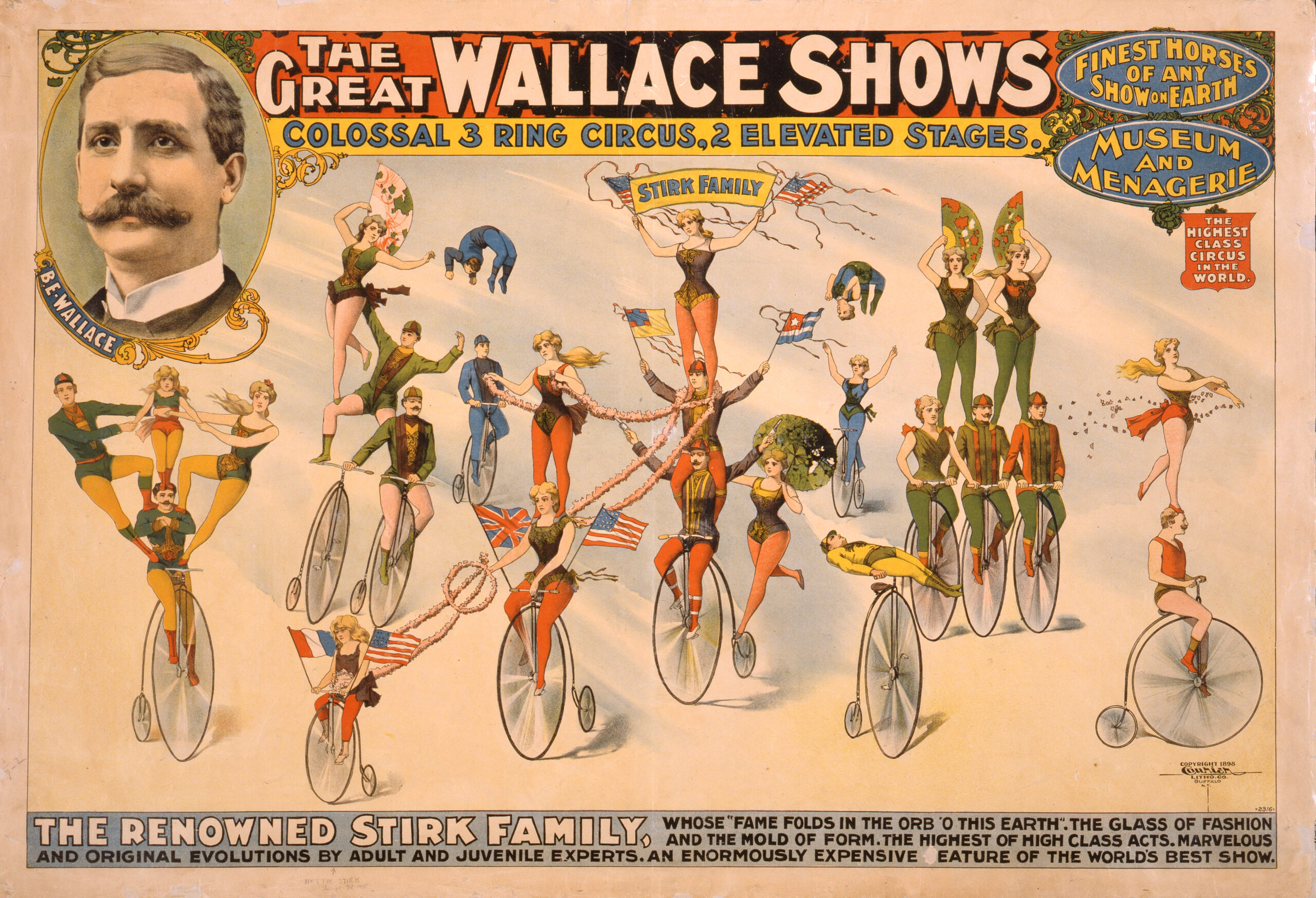

It was also thanks to the horse that circuses went from being sedentary to traveling. As early as 1830, in England, teams of several horses were pulling their heavy convoys. In 1870, Bamum launched its circus in the USA with 150 horses, 13 elephants and… gold-leafed parade floats.

Horses in the circus

The first circus horsemen and acrobats used harnessed and saddled horses. It wasn’t until around 1820 that acrobatics began to be performed on bareback horses.

Circus acrobatics

In 1825, Frenchman Jacques Gautier performed the first somersault on a horse with a seated return; in 1846, American John Glenroy performed the first somersault with a standing return; and twenty-six years later, his compatriot Robert Stickey performed the first double somersault. Orvin Davenport created the back-to-back somersault. The “jockey” act was created by Englishman Billy Bell: the jockey performs a series of jumps – astride, kneeling, standing – on the back of a galloping horse, starting from the track. A speciality from the East, “Cossack-style acrobatics”, presented by the djiguites, requires a track with reinforced benches, with unbroken horses galloping very fast, while the acrobats move in all positions around a saddle equipped with multiple handles; they even pass under the belly of their mount with a saber between their teeth, the horses crossing, in the end, barriers of fire.

From the West this time, “cowboy-style” acrobatics, with lots of shooting and lassoing exercises, was introduced to Europe in 1885 by Buffalo Bill, at the same time as rodeo.

The acrobatics mount (apart from the dashing, speedy djiguites and cowboys) is a heavy horse, regular in its gait, but endowed with solid impulsion: Friesian, Great Dane, Holsteiner, Percheron, Comtois, Boulonnais… In this discipline, mares are preferred for their calmer temperament and higher croup than males; notable exception: four imposing Boulonnais stallions are the partners of the fifth generation Gruss “quadruple jockey” at the “Cirque à l’ancienne” (Old-fashioned circus).

Comedians on horseback

The first comic squires, Saunders and Fortinelli, mimicked Philip Astley’s tailor and his assistant, who had a reputation in the army as poor riders. Their act consisted of an anthology of clumsiness and falls, the ridiculousness of which provoked hilarity. At Franconi’s, this entry was dubbed le Tailleur gascon or Rognolet et Passe-Carreau. Today, the exercise is performed by the single figure of a staggering “peasant”, standing on a galloping horse, gradually stripping off a considerable overlay of vests that round out his silhouette.

Equestrian pantomimes

Franconi also popularized large-scale pantomimes inspired by the military, featuring imposing figures on horseback: L’Empire des Cent jours, Austerlitz, Histoire d’un dragon, Bonaparte au pont d’Arcole, and others. Closer to home, others of Roman inspiration revived chariot races: Quo vadis at Sarrasani in Germany, Ben Hur in France at Radio Circus Gruss from 1962 to 1965, then at Jean Richard in 1975.

Free-roaming dressage

The first free-roaming dressage exercises in the early days of the circus consisted of individual acts such as Le Cheval savant, Le Cheval rapporteur, and Le Cheval faisant le mort. Small circuses still feature calculating or recalcitrant horses, answering yes or no with their heads.

Ensemble presentations in which several horses perform a series of right-hand passages, half-voltes, left-hand passages, pirouettes, passages in twos, threes or fours, waltzes, rear and so on. They were inaugurated around 1850 by Louis Soullier and Ernest Renz. Today, under most of the big tops, they remain the ultimate testimony to the golden age of the equestrian circus. Here, any breed can be used, the aim being to highlight the plasticity of the horses in a harmonious choreography, either by matching models and dresses, or, on the contrary, by playing on contrasts: mini and maxi (Falabellas and Shires), warm-blooded and cold-blooded (Arabians and Percherons), black and white, brown bay and light gray.

In the carousels, several groups of horses, usually of different coats and tota- User two dozen or more individuals, perform different figures in concert in a very spectacular overall picture.

The high school

Brought to the circus at the end of the 18th century by Antonio Franconi, who had learned it in Italy, this art was masterfully illustrated on the ring by his sons Henri and above all Laurent, as well as by his grandson Victor.

In the 19th century, the “god of the circus” in high school remained François Baucher. His pupils included Théodore Rancy and Caroline Loyo, the first high-school circus amazon. On the ring, contemporary horsewomen and horsemen, depending on their taste, temperament, or build, partner an English Thoroughbred or an Arabian – a Lippizan (as in Vienna) or an Andalusian (as in Jerez) – a Lusitano, a Ukrainian or an Akhal-Téké. Beards, Friesians and any saddle horse with sufficient blood and a good fit can shine perfectly in classical or fanciful high-school airs, depending on the skill, sensitivity, imagination, and particular talent of their master.

Performing horses

Circus stables are exclusively home to stallions. In all disciplines except acrobatics, stallions are preferred for their haughty character, fiery temperament, and natural ability to rear.

Horses arrive at the circus around the age of three. He gets used to being around other horses and then to trusting his trainer. He will become accustomed to the lunge rein and the whip (as aids), learn the ring, the call, the different gaits, how to back up, rear up, walk upright, make bows, lie down and even sit up, pay a “compliment”… The daily physical and psychological gymnastics required to learn his trade will forge an athlete’s body, giving him the balance and self-confidence that will enable him to shine on the track, whether as a soloist or in a group, mounted, on long reins or at liberty.

This skillful and patient training, always based on mutual respect between expert and pupil, enhances the latter’s natural attitudes and behaviors to make him not just a “circus horse”, but a true “horse artist” in the circus!